Suppose you’re on a game show and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the other two doors are goats. You pick a door. The host, who knows what’s behind the doors, must then open one of the two remaining doors and will only open a door containing the goat.

“Do you want to keep your choice or switch to the remaining door” the host says. What do you do? Do you switch? Does it even matter?

Give this some thought before you continue.

––––––

Here’s the weird answer – Yes, it does matter. It matters a lot. There’s only one clear choice: You should switch to the other door.

My guess is that when you thought about it you decided to stick to your original choice, figuring you had a 50/50 chance and because it feels better to stay with your original choice. Right?

Very wrong. Here’s why:

If you switch, you have a 66% chance of winning the car, while if you stick to your original choice you only have a 33% chance.

When you made the original guess you had a 33% chance of being correct (1 out of 3 doors). If you decide not to switch, those odds do not change even when you learned additional information about the doors after your original selection.

Meanwhile, you can capture the other 66% opportunity if you switch your pick to the two other doors. Makes sense, right? If you could have originally picked two doors, you would have had better odds. The host gives you that opportunity by allowing you to pick the other two doors, except he’s eliminated one by showing you the location of a goat. By picking the remaining door you capture the 66% opportunity.

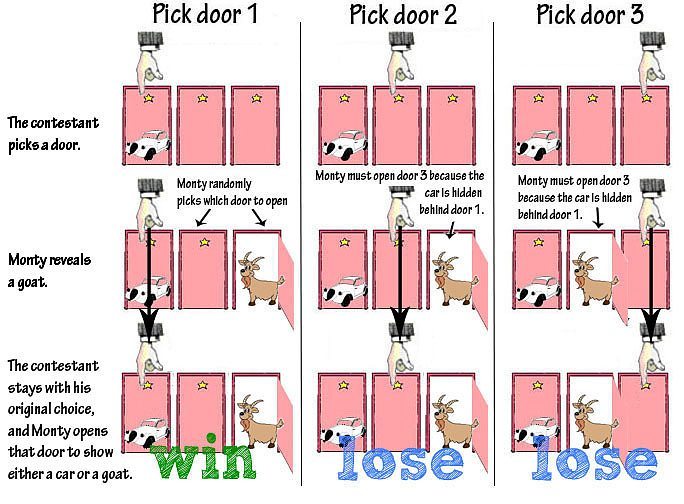

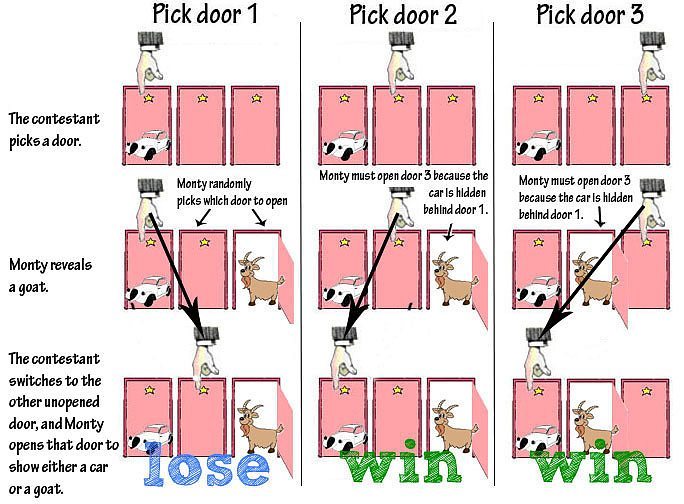

Here’s a graphical description of The Monty Hall Problem:

The Stay Decision

The Switch Decision

Images courtesy of the Math Forum.

The truth is, many of us would make the mistake of not switching. Even PHD mathematicians got caught up. Here is one response:

You are utterly incorrect about the game show question, and I hope this controversy will call some public attention to the serious national crisis in mathematical education. If you can admit your error, you will have contributed constructively towards the solution of a deplorable situation. How many irate mathematicians are needed to get you to change your mind? – E. Ray Bobo, Ph.D. Georgetown University

Ouch. I wonder if he wrote an apology letter.

Picking stock vs index investing

The simulation – and the resulting confusion – makes me wonder how well we understand other odds in our lives. What are the chances that a stock will go up or go down?

The stock market is a much more complicated version of the goat problem. Worse, there’s no host to help us along by revealing which investments are losers. But even if there were a host, would I listen and take the good advice?

This reasoning is part of why I switched from investing in individual stocks to investing in low cost index funds. I realized that the times I picked a stock that gained in value were just as random as the times I picked a stock that lost value. It all came down to luck. Operating with imperfect information and without a host (or being unable to take the good advice of a host) meant my individual investments were always going to be a game of chance.

Only later did I discover the founder of Vanguard, Jack Bogle, and his great investment advice:

Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack!”

It’s true. I’d rather keep what’s behind all three doors rather than worrying about which one has the prize.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He spends 10 minutes a month on Empower keeping track of his money. He’s also maxing out tax-advantaged accounts like 529 Plans to minimize his taxable income.

Happy to see a fellow “Boglehead” I’m a big fan of low cost index funds. There was a time back when I started investing that I thought I could time the market or pick individual stocks that would perform better. I have learned from those mistakes. My toughest lesson was when the internet bubble burst. At the time, everyone thought they were experts and everybody was making money until the bubble burst. Same with the 2008 recession, switched some investments to a more conservative ones and missed out on part of the bull market run. Now I just stick with index funds and stay the course. I will admit to investing in a few individual stocks with my “fun money” but only a small amount.

Yes, I’ve been a practicing Boglehead for awhile now, but not without making quite a few mistakes along the way. In fact, Monday’s post is about how I lost $10,000 on an investment. The experience finally sealed the deal for me when it comes to picking individual stocks. The thing is that I’m not even upset about losing the $10K (would I take it back? of course) but I just realized that the ideal life is a simple life. Since then, I’ve been on a path to keep my finances simple. I suspect I’ll also see greater returns as well.

As for “fun” money, I don’t think I’ll ever go back to individual public stocks but will certainly play with things like real estate and private investments.