Lawyers may belong to the only industry in the world where starting salaries cluster at two peaks along the landscape of income a junior lawyer can expect to receive out of law school.

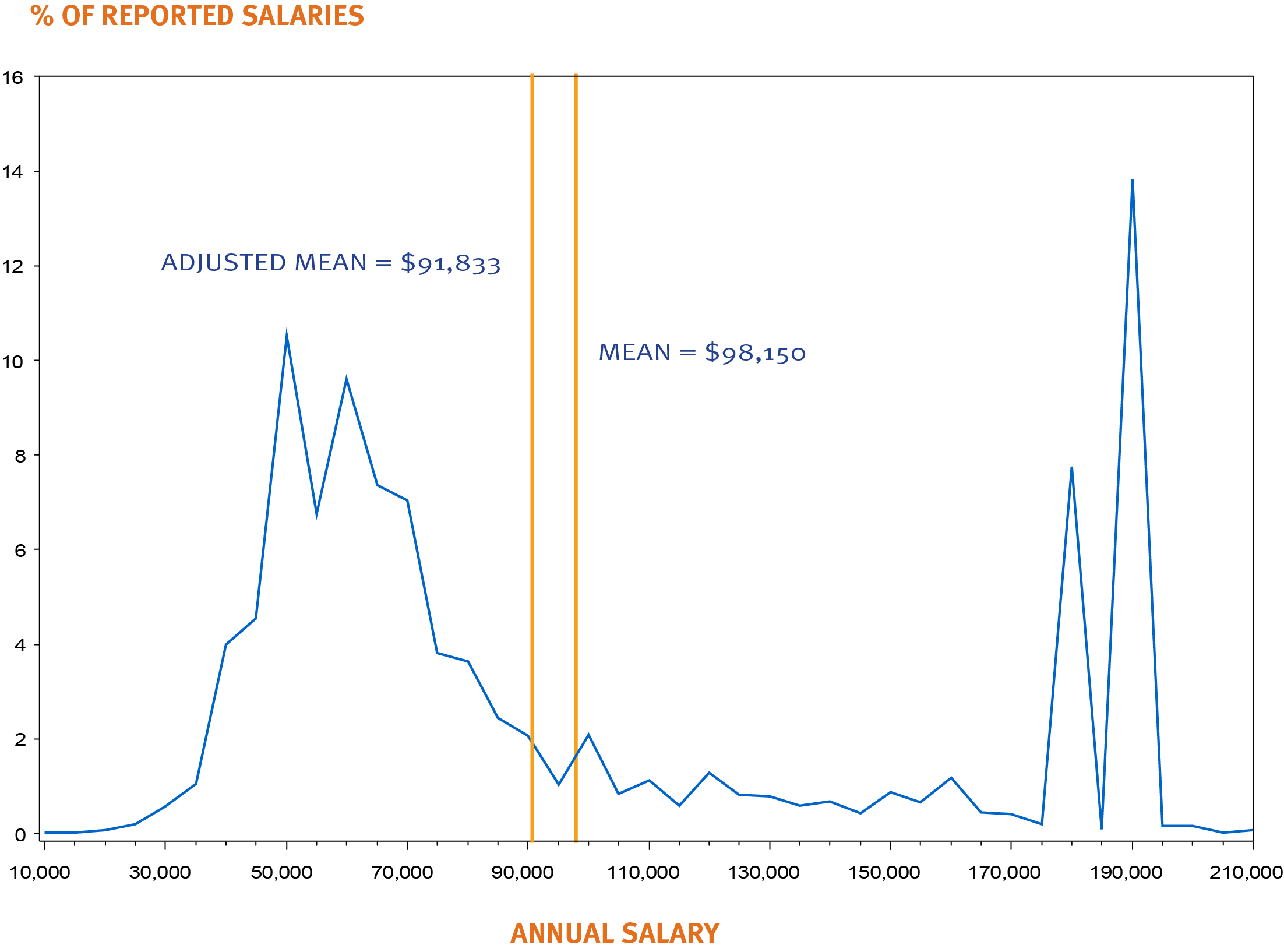

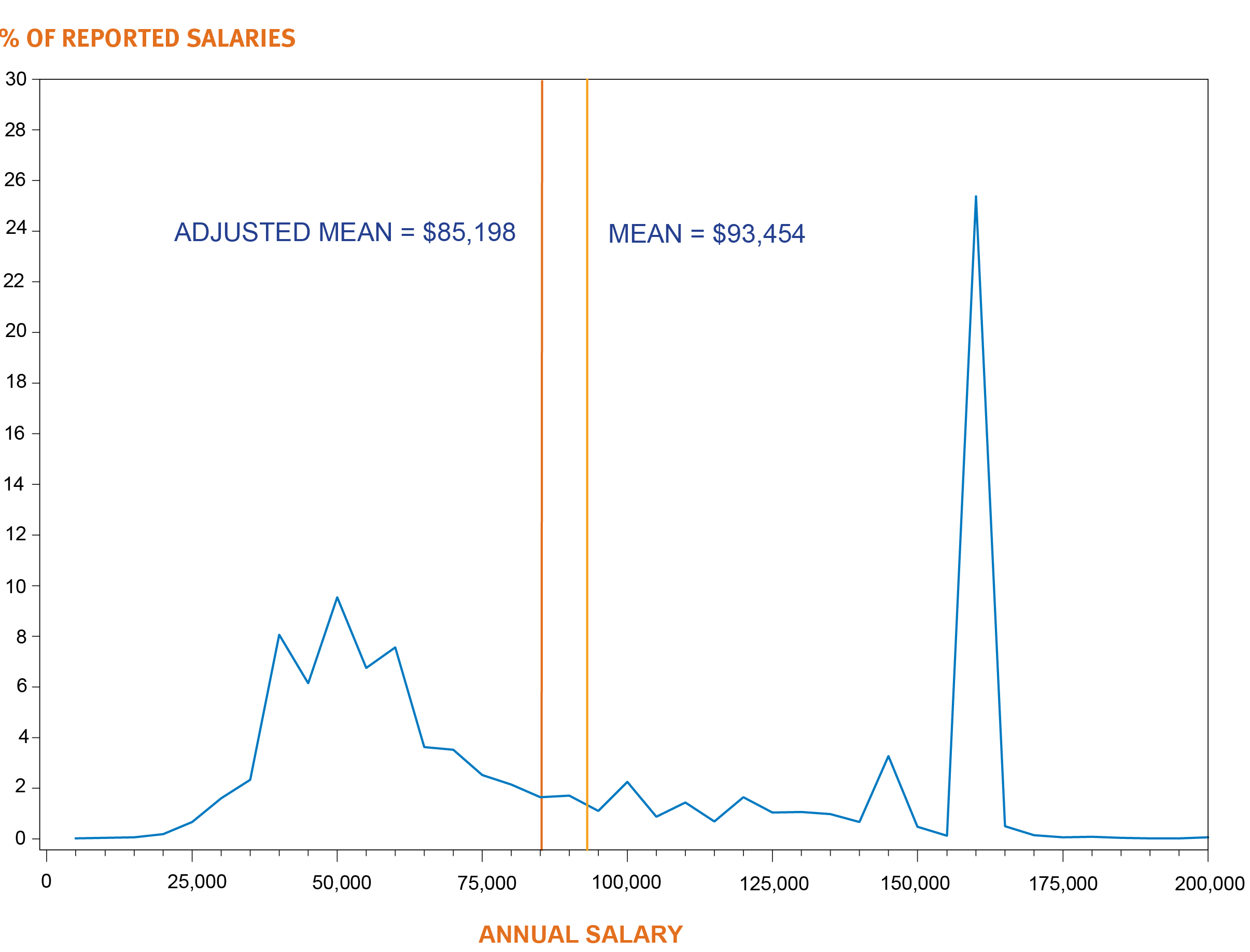

For those that aren’t familiar with the Bimodal Salary Distribution Curve, below is the latest chart from National Association for Law Placement, showing the starting salaries from the Class of 2018.

Class of 2018 – Salary distribution

Interestingly, the Class of 2018 is starting to see a Trimodal Salary Distribution Curve as not all firms are able to keep up with the most recent increase in the Biglaw associate pay scale. Around 7.7% of reported salaries landed at $180,000, while 13.8% said that they were getting paid the 2018 market standard of $190,000.

Meanwhile, the other large distribution of starting salaries falls in the $50,000 – $60,000 range, which is the salary an assistant district attorney in NYC might expect to earn.

The chart is probably the single most important organization of data to consider when discussing lawyers and personal finance since lawyers start at such dramatically different points of income.

But before we talk too much about what you can do with the income you have, I did some digging and thought it would be interesting to write a little about the history of that curve.

Looking back: Has it always been this way?

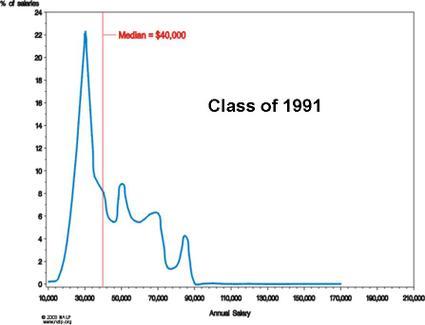

Twenty-five years ago the legal industry had a much different distribution of starting salaries. Those salaries followed a typical mountain peak followed by a sloping curve, which is generally what you’d expect to see for starting salaries (i.e. almost everyone is clustered at the lower end of the range with a few all-stars finding a higher salary).

The 1991 chart looks like a normal salary distribution with the median slightly ahead of the largest peak thanks to some lawyers that managed to command salaries in the $70-$90K range upon graduation.

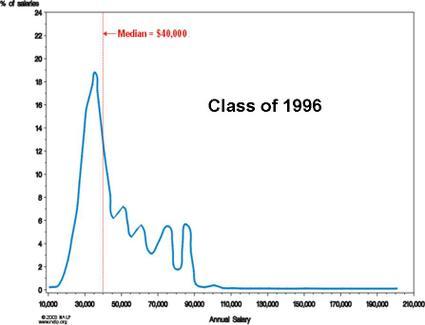

By 1996, there really hadn’t been much of a change except to note that a slightly lower percentage is clustered at the beginning (i.e. smaller mountain peak) which suggests that more lawyers were finding higher paying jobs.

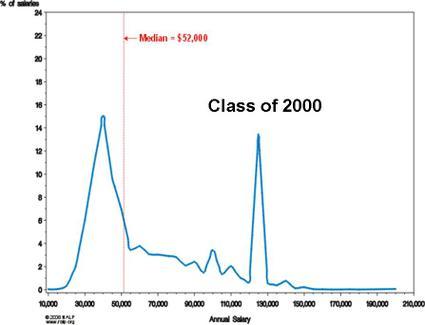

But only four years later, we have the fully developed twin mountain system that we live in today.

What caused the shift?

According to William D. Henderson, the shift to a bimodal salary distribution was caused by two factors: (1) the growth of the corporate legal services market and (2) the adherence to the “Cravath” system which aims to hire the top graduates from the top schools to create an elite law firm.

Ironically, Cravath’s “system” for getting the best and brightest has now been adopted by every large law firm that provides full-service highly-specialized legal services, with the result being that nearly all “Biglaw” firms follow Cravath when it comes to salary.

On one hand, you could argue that Cravath gave up on the idea of differentiating itself from its peers or, on the other hand, you could argue that every other major law firm has adopted the model without truly understanding its intent.

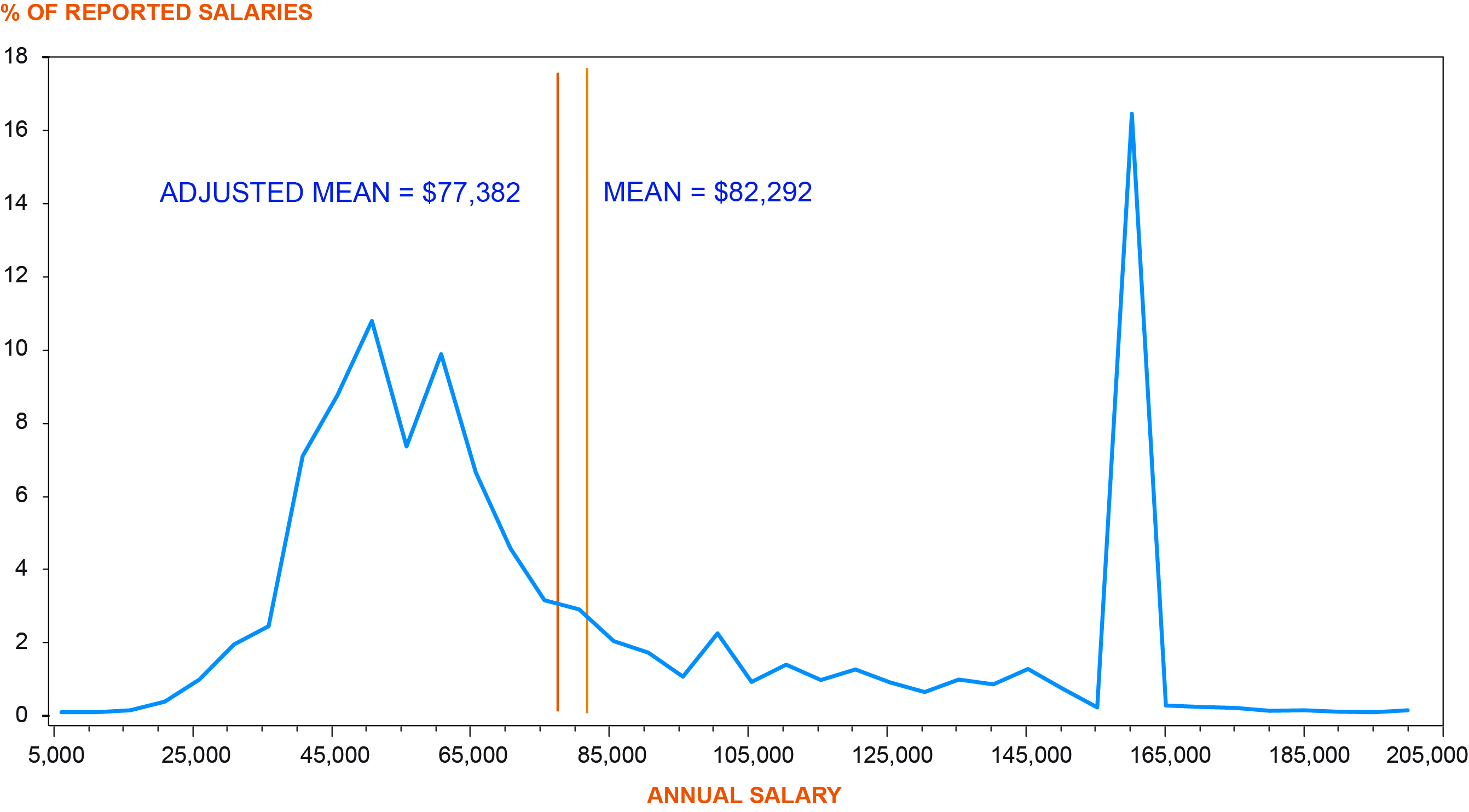

Regardless of how we got here, the dual track system for lawyers seems here to stay. Since 2010, we’ve come to expect a bimodal salary distribution as shown in the following charts from 2009 and 2014.

Class of 2009 – Salary distribution

Class of 2014 – Salary distribution

Law students – Bimodal salaries

What does this mean if you’re in law school?

First, you must understand that the bimodal salary distribution curve applies to you. While you might end up with a high paying job, you might end up in the other half of the salary distribution curve.

More importantly, look at how many jobs there are in the middle. Almost none. This is lost on a lot of law students who think they may not end up with a high paying “biglaw salary” but also assume they won’t end up with a low paying salary either. The real glut in legal salaries is everything between $65,000 and Biglaw.

Lawyers have been cramming this information down the throats of law students and pre-law students for the past few years (decade?), so you would think that everyone is aware of the potentially bleak financial outlook for some lawyers but I still run across pre-law students all the time that think all lawyers are rich.

Regardless, if you’re in law school, you need to buckle down on law school expenses in a big way. Forget about taking the bar trip. While law school can be a lot of fun (well – you’re not working), it’s more important than ever to develop a financial plan. Don’t assume that your law school loans will eventually be forgiven either. The government is a step ahead of you on that one and it’s not at all clear that following the IBR/REPAYE path is a great deal.

Practicing lawyers – Bimodal salaries

How does the salary distribution curve affect you if you’re a practicing lawyer?

Well, for one, it’s only a representation of starting salaries. Many lawyers that start on the lower end of the cluster end up growing their salaries over time. The average lawyer salary is still in the six figures, which means that your income will likely go up over time if you’re starting at the lower end of the bimodal salary distribution curve.

Planning for a gradual increase in your income is important because it may change your strategy with respect to things like your income-driven repayment plan calculations. Many law students or new lawyers make calculations of their student loan payments thinking they’ll be making $50,000 for the foreseeable future (i.e. throughout their entire repayment plan). When you realize that your salary is likely to rise over time, you will also see that your student loan payments will increase as well. While that might seem fine – more money, bigger payments – it could make you second guess whether forgiveness is the likely outcome for your student loans in the long term.

For Biglaw lawyers, the same is true. The chart is only a representation of starting salaries. Will you still be in Biglaw after three years? five years? 10 years? Most will leave Biglaw. When you leave Biglaw, your salary could very well revert to the mean. That won’t be a problem if you took advantage of your Biglaw years to pay off your debt and build up a war chest.

The takeaway is that neither end of the spectrum lasts forever, so planning your financial future on an income of either $60,000 or $225,000 has some serious flaws.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He spends 10 minutes a month on Empower keeping track of his money and is currently looking for additional lenders to add to Biglaw Investor’s JD Mortgage service which connects readers with lenders offering special mortgages for high-income professionals.

I’m not sure this is all that unique to lawyers. Tech has a similar situation where the best and the brightest get the extreme salaries in Silicon Valley. Everyone else gets a much more average though still high for he general populace salary. This is why I once stated on my blog I’d never want my kid to be a pure computer science student. To stand out you have to be the best. It sounds like law has the same stratification.

That would be really interesting if it were the case. Can you point me to some data/charts showing a bimodal salary distribution for tech employees? I would have guessed that tech follows a normal bell-shaped curve where a higher-percentage cluster around the lower paying salaries and then you have a nice downward sloping curve as the best and brightest get the extreme Silicon Valley salaries. But maybe there’s a second peak? Do all the big firms like Google/Apple/Facebook pay starting salaries to tech engineers at the same standard amount, sort of like making it into “Big Tech”?

“Do all the big firms like Google/Apple/Facebook pay starting salaries to tech engineers at the same standard amount, sort of like making it into “Big Tech”?”

That’s exactly the case, yes.

There is now amongst technology companies an elite group which pays far more than pretty much every other set of technology company out there. It’s not unheard of for kids to be getting $130-160k/year total compensation packages their first year out of university.

Compare that to the bulk of orher companies offering $60-80k or less starting and you’ll begin to see there’s a dichotomy, with BigTech (in addition to large private startups and quantitative financial firms) paying within a tight upper range.

Where this phenomenon stops looking like that of biglaw’s is in the proportions. Whilst 18-20% of law school grads may land into biglaw jobs, the proportion of technical graduates that land these coveted bigtech jobs is far lower. So as per the graph, rather than bigtech jobs being a sharp spike, they would be more of a meaningful hump on the right side.

I don’t think I was aware of the bimodal salary distribution when I started law school…that was over a decade ago though. I knew I wasn’t getting the big salary early on but figured there was something in the middle. However, I soon realized there wasn’t really anything in the middle, you would either fall in the peak with the high salary or the one with the lower salary. I would hope prospective students are much more educated before they make the decision to take on debt to go to law school. I was lucky to get a decent paying job in government with good benefits. A friend asked me why I didn’t go to the private sector assuming they always pay more. When I graduated, I saw plenty of small law firms offering $40k for an entry level attorney (in NYC). I made more than that without the law degree.

Excellent point. I updated the article to reflect your comment about the lack of salaries in the middle. I had the same assumption in law school. I figured I might not end up at the top but that surely there would be plenty of jobs in the middle. That’s probably the biggest part of the discussion that is missing – very few people land out of law school earning exactly $100,000. Thanks for bringing it up.

“Many lawyers that start on the lower end of the cluster end up growing their salaries over time.”

I’ll warn that many lawyers that start on the higher end of the cluster end up having their salaries fall over time, as well…..fall off partner track, and you can see your salary fall precipitously, which is why it’s a good idea to pay off debt/budget wisely when you’re making a lot so that you don’t suffer if you end up making far less later on. (I speak from experience — my first 2 post-BigLaw jobs paid far less than my starting salary at my BigLaw firm, while my currently position’s salary is still below that BigLaw salary but the bonuses are far, FAR better and more than make up for it.)

Great point chadnudj. I updated the article to reflect your comment. Not sure why I forgot to mention that high earners also revert to the mean and it’d be silly not to plan for that. Interesting that now your total compensation exceeds Biglaw levels. How long did that take once you left Biglaw?

6 years, roughly? I’m certainly not a poster boy for how to do things — this is my third position in those 6 years. I left one firm that wasn’t a good fit after about 18 months; was at another for 2.5 years before the firm downsized/merged with another (and let me go); out of work for 6 months; then landed my current position at a complex litigation plaintiffs’ firm, where the salary is roughly at where my big law starting salary was, but bonuses are large (which is pretty standard at plaintiffs’ firms, so long as things are going well, which they are).

I graduated from law school in 2001 and went into biglaw, so I was in school and applying for biglaw jobs right when the shift into the bimodal distribution occurred. The shift happened all at once during the first six months of 2000. When I started law school in 1998, the biggest biglaw firms paid around $90K for first years, but this was only the largest firms and even then only in their NYC and maybe California offices. Most of those firms had different salaries (usually $10-15K less) for the rest of the country. Even then, it was only the most prestigious firms (maybe 50-75 firms if that) who paid so much. The overwhelming majority of “biglaw” firms paid something in the range of $75-80K to first years. In the late 1990’s, however, silicon valley and venture capital were booming and pilfering many of the law students who otherwise would have gone into biglaw by offering more money. To combat this, one relatively small firm based in SF/SV (one that people may not have even considered “biglaw” — I want to say Gunderson something but don’t remember), all of sudden raised its first year salaries to $125K and within the next six months just about every medium to large law firm with offices in major cities (including both the ones that had been paying $90K and those that were paying $75-80K) matched that salary scale. Moreover, I think almost all of them made salaries the same across all offices. So instead of a NYC salary scale and a scale for the rest of the country, biglaw salaries became the same throughout the country. I remember that when I accepted a biglaw summer associate position in fall 1999 for summer 2000, my salary was going to be $1800 per week, but then a few months later I received a letter saying my salary was being increased to $2400.

Thanks TMat, always great to hear a story from someone who was in the trenches at the time. Certainly sounds like it must have been a weird time to see salaries jumping into place like that.

I did a little further research and it looks like Davis Polk is the first the moved starting salaries from $105K to $125K in February 2000. The articles I found didn’t say if they were matching a firm from the West Coat, but it makes sense to me that a NY firm would match any raise by a firm out in San Francisco and then all the NY firms would fall in line. Salaries stayed at $125K until February 2006 when Sullivan & Cromwell moved them up to $145K.

I’m always amazed that salaries in NYC aren’t slightly higher than in other markets (or maybe NYC/SF salaries at one level and the rest slightly lower). To me, that says that there’s another force that drives associates to those markets since they effectively make less than their peers. I would guess that force is the desire of millennials to live in NYC/SF.

I think that is probably a big reason why people accept the same salary to be in NY/SF, but ultimately, they don’t have a lot of choice. I don’t have numbers, but I would guess that NY/SF probably account for more than half of the top biglaw jobs across the country. And for the most part, I don’t think firms there care whether you have much of a connection to the city. On the other hand, to get a biglaw job in cities with smaller legal communities, particularly popular cities (California and Florida cities, Miami, Seattle, and others), candidates often have to demonstrate a connection to the city to get a biglaw job. By the way, I found the article below that discusses the raises around the turn of the century. It states that the raises started at Gunderson in Silicon Valley. The quote from the Brobeck associate that the salary increases are going to make firm associates think twice about leaving because “a lot of dot-coms fail,” made me chuckle considering that Brobeck actually failed around two years later.

https://www.nytimes.com/2000/02/02/business/law-firms-pay-soars-to-stem-dot-com-defections.html

It was an interesting time. I graduated in 2000. Most of us saw our starting salaries go up 30-35K before we even started work. It happened pretty much as TMat described it. If you were able to navigate the terrain, it set up a crazy ride where you could enter the legal profession and never make less than 6 figures. But I think it fundamentally changed the character of a lot of firms and the profession. Enter the 2 tier partnerships, the extended track to partnership, the ever increasing “what did you do for me lately” nature of partnerships, etc. I exited BigLaw for its equivalent in-house not by choice but am so glad I did about a decade ago. It isn’t without its headaches, but it’s been the right choice for me.

What a great post, the information is well organized and very comprehensive. I can imagine the effort you put into this and especially appreciate you sharing it. I really appreciate the info and ideas. I love your blog!

Well I thought this was super weird at first, but once you mentioned the Cravath thing I suppose it’s not that weird at all, eh? It actually looks pretty much exactly like all the old graphs, except with a big spike where all the “Cravath lawyers” are.

Well-written, including with the update for the recent 2018 moves. I’ve always thought these charts should factor in bonuses too, though, since the amounts are pretty standard.

Vital for people who are on the right side of the chart to know it isn’t forever. So many sad stories of folks who get into Biglaw, put off paying their student loans etc. because they figure they at least have 7-8 years in Biglaw (i.e., until the partnership culling starts to happen). Lo and behold, 2, 3, 4 years later, whether by choice or not, they find themselves on the left side of the graph (or off the graph entirely, if they leave the profession, as many people do).

That’s a good point about bonuses. They should be included in the chart. That would widen the gap even further as you’re unlikely to get a $7,500 bonus (current amount being paid to first year Biglaw associates) if you’re working as an assistant district attorney.

While it varies from year to year and firm to firm, the overall attrition rate at biglaw firms is 15-20% – as in, every year one out of every six attorneys leaves.

Out of 100 attorneys, after four years only 40-50 are left, and by year eight, 17-27 remain. Roughly one in six even survive long enough to be considered for partner, and only about 3-10% make that leap.

The odds of making partner are indeed slim. What a lot of law students and junior lawyers fail to realize is that once they get into Biglaw they’ll probably self select as someone who doesn’t want to make partner anyway.

from my experience roughly as many lawyers leave voluntarily as involuntarily – particularly after a few years.

The other problem is that you don’t spend 7 years being a good attorney, and suddenly become partner material. It takes years to lay the groundwork to become a partner, and you need to start working towards becoming a partner as early as possible, but certainly by your 4th year.

This blog is incredible! I am by no means a newly minted lawyer (more than a decade of BigLaw and public sector law), but I am learning so much reading through your articles. I am going to recommend this site to all my lawyer friends, and all the law students that i counsel. I wish I had had this site when I started out in BigLaw! I think I made some pretty good choices back while I was at the firm (aggressively paid off six-figure law school student loan debt, bought a house, no car, funded six-figure 401(k), etc.) but I also made some missteps (no financial plan, expensive whole life insurance policy, no understanding of investing, etc.). I didn’t know of any one source for the kind of easily accessible and understandable information you’re providing here — and as a single African-American woman, this stuff just wasn’t common knowledge in my network or community. Even though I think I have done well for myself overall, this site has inspired and empowered me to take complete control over my personal finances and to fill some gaps (especially as it relates to tax-advantaged savings) that are holding me back. My sincere thanks for all the time, attention, and care you’re bringing to this labor of love! It sounds cliche — but you really are making a difference in the world!

P.S. It’s the former teacher in me — but I think you accidentally say “effect” where you mean “affect” in the intro to your write-up above.

Thank you for such a nice comment! Your thoughts mirror my own. I built this site because it’s what I wish I had when I was starting in Biglaw many years ago. We’ve helped thousands of people over the years but it still feels like we’re just getting started. I shared your comment with the internal team as they’ll appreciate the encouragement!

p.s. Love the grammar comment. We’re always trying to get better. I’ll fix that now.

Well, I got into this article while nursing the wounds that 40 years in law have created. To be concise, I should have gotten that MBA. Law wasn’t worth even half my efforts. Somehow I thought it would be the red carpet, like in the mid 1960’s – a license and a pulse would get you multiple decent offers. These hires, 15 years my senior, were the azzhats that cluttered my career, offering low wages and insufferable conditions they never experienced.

Thanks for the comment Eddie. I don’t think you’re alone in those thoughts.

“Well, for one, it’s only a representation of starting salaries. Many lawyers that start on the lower end of the cluster end up growing their salaries over time. The average lawyer salary is still in the six figures, which means that your income will likely go up over time if you’re starting at the lower end of the bimodal salary distribution curve.”

First of all, I love your blog! Thanks for the insight. But I guess my question is, can you provide some anecdotal context to salary growth for non big-law lawyers? While I know government lawyers gradually get a yearly increase per a step scale, non-big law lawyers in the private sector seem to follow a less linear path. My anecdotal observation is that there seems to be this subset of lawyers who toil away for ten years at these small, $50k/year firms and still only take in a marginally higher salary then what they first earned as young associates. Generally speaking, is there a demand for mid-career non-big law lawyers in roles that pay ~$100k? Would the six figure average salary (a number you think indicates salary progression across the board) be attributed to these $50k lawyers moving to regional mid-size firms (think insurance defense, employment law, etc)?