(Update: Following publication of this article, Travis from Student Loan Planner reached out to me (see his comment below). After speaking to him, I have a follow-up post coming on this topic. While married filing separately doesn’t work for us, there may be another option to make PSLF work. I’ll update this comment with a link to the follow-up post once it’s published.)

The Public Service Loan Forgiveness program looks great on paper. If you work in public interest for 10 years, your loans are forgiven. It sounds simple, but unfortunately the program is much more complicated underneath the surface. After a lot of thought, we’ve decided to abandon the program and will be paying back my fiancé’s student loans despite being eligible for PSLF. Here’s our story of why we’re making that choice.

First, some background facts. I’m working in Biglaw. She’s working in public service and has $125,000 in student loans. She’s made four years of qualifying payments. We’re getting married this year.

When payments go down, taxes go up

As many of you know, PSLF is a forgiveness program layered on top of one of the Income Driven Repayment (IDR) plans. IDR is the broad category that includes the more familiar repayment plans like: Income Based Repayment (IBR), Income Contingent Repayment (ICR), Pay As You Earn (PAYE) and its new version (REPAYE). If you make 120 qualifying payments under one of the qualifying plans above, PSLF swoops in and forgives your loans. No taxes are due on the forgiven amount.

The first thing I noticed about the various IDR plans is that they’re not based on the borrower’s income. When you’re married, the repayment plans instinctively want to look at the couple’s combined income to determine the appropriate monthly payment. Intuitively this doesn’t seem fair since the it shifts the repayment burden to the spouse (regardless of the spouse’s income). Under our combined income, any of the IDR repayment plans result in us making payments equal to the standard 10-year repayment plan. Our combined income is simply too high.

Let’s pause there to let that point sink in.

Once married, if we make payments under our combined income, even under the IDR plans, we’ll be paying as if we’re making the standard 10 year repayment.

The way around this problem is to file taxes as married filing separately (MFS). Typically, a married couple will file jointly (MFJ) and there are very few instances were a couple would even consider MFS. This is one of those situations.

If you are married filing separately, the repayment plans will calculate the monthly repayment amount based on the borrower’s income. In other words, if we MFS, we’ll only have to make payments based on her adjusted gross income.

Therefore, determining whether only one income or both incomes are counted in calculating your payments is completely driven by your tax filing status.

That sounds great. If we switch to MFS, our monthly payments will plummet because they’ll be based on her income alone.

It gets even better. I think I can get those payments down to zero (or close). She has access to both a 401(k) and a 457(b) account. By shifting incomes, we can reduce her adjusted gross income to ridiculously low levels by maxing out her pre-tax accounts.

Student loan payments are based on calculating “discretionary income” which is your adjusted gross income minus 150% of the poverty line. By reducing her income so much, we can effectively reduce her payments to dollars a month (my calculations show we could make monthly payments as low as $4 a month).

The problem?

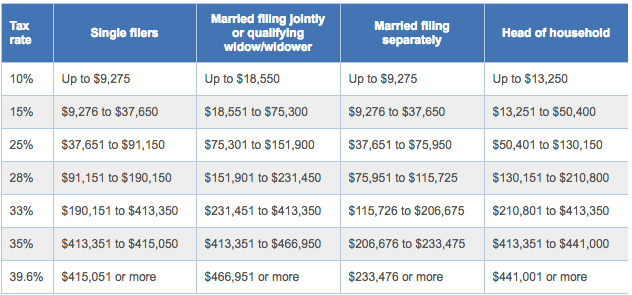

Married filing separately is a bitch. The government does not want you to file separately. Take a look at the below tax brackets comparing MFJ to MFS.

The key here is to notice when the 25%, 28% and 33% tax brackets kick in. You’d assume that MFS has the same tax brackets as filing single, but they don’t! It’s actually punitive to file separately.

As a single filer, I wouldn’t start paying a 33% tax rate until my adjusted gross income reached $190,150. Under MFS, the 33% rate starts at $115,725. That’s an additional $3,721 in extra taxes right there. It gets worse as you go up the tax bracket. Starting at $233,475 you are paying the highest tax rate at 39.6%.

The punitive tax rates are the most overlooked part of filing separately. If you remember any part of this article, remember that married filing separately isn’t the same as having two people file their tax returns as single.

It gets worse when you factor in the various other benefits that are eliminated when you file separately including: (i) child and dependent care tax credit; (ii) Roth IRA contributions; (iii) traditional IRA contributions; (iv) deduction of net capital losses; (v) student loan interest deduction; and (vi) deduction of college tuition expenses (and there are more).

On top of that, MFS taxpayers must both claim the standard deduction or must both itemize their deductions. You can’t have one spouse claim the standard deduction (i.e. her) while the other spouse itemizes (i.e. me).

How much damage would this cause on our taxes? It’s hard to know for sure and frankly I don’t need to see a precise number. It’s bad. Based on my estimates, we’d likely pay over $23,000 in additional taxes than we would otherwise pay if we filed jointly.

At this point it feels like we’re saving money in one area (student loan payments) only to spend more money in another (taxes). Frankly, I’d rather pay off the loan and be done with it rather than make minimal student loan payments while paying extra taxes hoping the forgiveness kicks in at the right time.

Take away points

Here’s the important points from the above discussion:

- Payments under student loan repayment plans are based on your tax filing status. If you’re married filing jointly, it’s based on your combined income. If you’re married filing separately, it’s based on your individual income (except for REPAYE which always looks at your combined income).

- Married Filing Separately is not the same as two individuals filing single. There are major penalties for MFS, including punitive tax brackets and loss of many deductions.

- If we MFS, we could reduce her income such that her student loan payments would almost be zero. PSLF would then forgive the loans after six years.

- If we MFS, our tax bill would go up by nearly $23,000 a year.

In exchange for no student loan payments, our taxes would increase by $23,000. What’s $23,000 times six years (the amount of time we have left to qualify for PSLF). It’s $138,000. That’s more than the entire balance of the loans.

No thanks. I don’t want to pay increased taxes equal to what we’d pay if we paid off the loan with the hope that PSLF is still around and we qualify in the future. I’d rather buckle down and pay off the loans quickly and keep the tax benefits.

Therefore, it seems pretty straightforward to me that we need to abandon PSLF. It sounded like a great program in theory, but in reality it’s not a good deal for us.

Here’s some other considerations to keep in mind:

1) PSLF Might Disappear. I’m not overly concerned that PSLF could disappear in the next six years, but who knows right? Why rely on a government program when you don’t need it? I see no reason to take on the risk that PSLF is still around in six years if I don’t need to.

2) Value of Freedom. It’s hard to put a price on freedom. If we pay off the loans quickly, it’ll be a tough slog, but if we wait for PSLF to kick in we need six more years of doing the same thing. That gives us no flexibility to change jobs (i.e. leave public service). Each year it gets harder to leave the program as well. You’re not going to make it to year 9 and then all of a sudden decide to pay off the debt.

3) Changing Incomes. The $23,000 annual tax increase assumes our incomes will remain the same. They could easily plummet. If income falls, the tax penalty won’t be as large. Our incomes could also increase, making the tax penalty greater. It’s hard to say which way this will go, but I’d like to err on the optimistic side of assuming our incomes will go up. I’m not willing to shelter myself in the PSLF program on the risk that my income decreases in the future. I’d rather we were driving the bus on these types of decisions. Paying off the loans puts the decision in our hands.

Next steps

Armed with this information, the conclusion for us is clear. We will be abandoning the PSLF program and trying to rapidly pay off the last of our student loan debt. It’s never fun to pay off debt, but the other side looks much brighter. Plus, could we pay this off today with liquidated investments? Sure we could! But that’s not the point. Those other accounts have different purposes. I’m not robbing the car fund to pay off these loans. Better that we buckle down, refinance the student loans and treat the debt like the emergency it is.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He is always negotiating better student loan refinancing bonuses for readers of the site.

The 10 years for PSLF is my main problem with it as a route for lawyers. Unlike doctors, our profession is just super unstable. A doctor is also required to do several years of residency (sometimes as many as 6 or 7 years depending on the speciality), and is basically guaranteed a job that qualifies as public service, so it doesn’t seem very hard to get the 10 years of PSLF.

I graduated law school in 2013 and went big law, then state gig. Who knows how long I’ll stick it out where I am now. I’ve got friends who’ve already had 3 or 4 different gigs during that time. I just don’t think I could count on any program for 10 years as a lawyer that required me to stay in one type of job, especially given the uncertainty we face in our profession.

The effect of combining incomes is also something I didn’t think about. I feel like most lawyers marry significant others that make good incomes (for us, we’re a JD+DDS couple), which basically would then force you to do married filing separately.

You may want to consider talking to Travis over at studentloanplanner (he has another site also, Millennial Moola). He’s really knowledgeable in this sort of thing and might be able to give you some advice on the best route to take.

How many gigs have you had since you graduated law school? How many has your fiance had?

That’s interesting that you see the government job as unstable. Do you mean unstable in the sense that you may want to leave or unstable in the sense that the job may not be available even if you wanted to stay? From my anecdotal evidence, the government legal jobs are more stable and so a reasonable route for lawyers that need to rely on PSLF. Of course, whether you want to stay in the job is an entirely different scenario!

The effect of combining incomes is really the sad part of the story. I don’t think many law students are thinking about it (and why would they?) but the way the program works heavily penalizes married couples. Worse, the idea that you can just MFS and magically fix the problem of a dual-income household overlooks the damaging effect MFS will have on your taxes.

Thanks for the recommendation on reaching out to Travis. I’ll send him this article and see what he thinks. Based on my research, it’s pretty clear that we’re abandoning PSLF.

Between the two of us, we’ve had three different jobs, so there hasn’t been a lot of turnover so far.

Forgot to mention earlier that Michael over at Student Loan Sherpa is also a pretty good resource for student loan information (there’s a forum and he also answers questions from readers on the blog). Plus, he’s also an attorney with law school debt so he can probably relate…

I’ll admit that a government job is much more stable, although I’m not quite sure how stable it really is. Even now, I always feel like I could be let go at any moment. During the financial crisis, my government office saw the number of attorneys drop. Whether that was because of the economy or because of other factors, I’m not quite sure, and I hope I don’t ever have to find out.

But really, when I think of unstable, I mean that there’s a high chance that you jump to a new gig. 10 years in any type of job in the legal world is a really long time, in my opinion. It’s not quite the same as compared to doctors, who are often required to do 6+ years in a residency in order to make the big bucks later on. A lot of people starting out in government could easily end up jumping to private practice or in-house, and needing to stick around in order to keep my PSLF is just a position I’d hate to be in.

I see, thanks for leaving that comment. I was curious if the first point is true among government lawyers. In my experience, you can stick around for pretty much as long as want (assuming you are competent) but it would be a pretty devastating blow to do 8 years of PSLF and then find your only options are working in a private firm.

The second point resonates with me and is especially true for law students and new attorneys. When you have no idea what a job is like, you’re hanging your hat on a lot by showing up at a place and expecting to be there for 10 years. In fact, that is one of the WORST things about student loan debt. I hate how much anxiety it causes among lawyers because they feel shackled to a particular path. Even if you end up liking your government job, you feel very anxious when you start because you feel that you have to keep it for 10 years.

I hope more of them will find this site and figure out ways to eliminate the student loans to relieve that anxiety.

I graduated back in 2007 when the PSLF first came out. I was working in public service and qualified and my wife had a relatively low income, but running the numbers, it still didn’t work out. However, REPAYE and PAYE weren’t available at the time…only IBR I believe. Combined we made a little over $90k (in NYC so that isn’t much) and I’d be paying the standard payment or close to it. I don’t think I knew or took into account that it was based on adjusted gross income so I only calculated it based on our gross income. But as our income grew, I’m sure we’d be paying the standard payments at some point soon and I wanted more flexibility with money at that point so opted for extended payments. My interest rates are also incredibly low so that might have been another factor.

What if your fiancé stays with the PSLF and makes the standard payments after you guys get married? Wouldn’t she still have some loan to forgive at the end of 10 years since she was making payments based on one of the income driven payment plans for the first 4 years?

When PSLF very first came out, I too was married. However, at that time you could just submit your income by turning in a pay stub. That is no longer an option as you are required to submit your taxes if you filed. You can adjust your dependents afterwards but it takes away the option of only being based on one income. That marriage did end in divorce and I have a serious boyfriend now. I’ve actually said I didn’t want to get married until my 10 years was up. That’s another 4 years. By then, his son will be close to college age and we might consider not getting married then either because of the financial penalty when considering qualifying for federal money for school. If he isn’t my kid’s father and I’m not his kid’s mother, I feel our income shouldn’t count toward that. Similar to if we were married when the debt was obtained, and got divorced, part of that debt could be ordered as the other person’s. However, if we weren’t married when it was obtained, then at least in my state it cannot be considered half your debt too. I think they just keep adding requirements in hopes most people leave or don’t end up qualifying.

I haven’t been through the full process yet, but I think you are able to use your pay stub. I know for certain that you are able to certify your income for repayment using pay stubs; the PSLF certification form simply requires your employer to sign; and the PSLF Application doesn’t mention requiring your tax return. Is this something that they ask for after you apply for forgiveness?

The current forms are:

IDR recertification: https://static.studentloans.gov/images/idrPreview.pdf

PSLF Application: https://studentaid.gov/announcements-events/fedloan-stop-servicing-loans

I’m working toward PSFL, married, just had my first child, file taxes separately, and do not have my spouse’s income counted toward my payments. It is working out quite well as we are able to get my payments down to almost nothing by paying pre-taxed monies for childcare, health care, and retirement savings. We do lose some tax breaks by not filing jointly, but this loss is outweighed by my student loan payment savings. Also, my payment were cut in half (almost) when I had our child. Fingers crossed that this can keep up!

Doing good isn’t always easy

Hey Josh! My girlfriend and I abandoned PSLF too for her med school loans, but I think it’s a bit more complicated here than it was for us. She consolidated at the end of residency because she didn’t understand the PSLF program at the time, so she lost out on 4 years worth of credit there from creating a new loan. She also used 6 months of forbearance, and the servicer she had lost proof that she had 2.5 years of PSLF credit. Hence, we said to heck with it and refinanced into a 2.2% 5 year variable rate and are paying it off in a year because her debt is relatively low compared to her income as an attending doctor.

I ran a simulation of your numbers into my proprietary spreadsheet I built that I use in student loan consults with clients. Here’s what I found. I’m assuming your income is $180,000 and grows at the rate of inflation. I assume hers is $60,000 and grows at the same rate. I’m using married filing separately as my tax assumption, and I’m taking into account the 4 years of credit she has to the PSLF program.

Assuming your wife is eligible for PAYE and could file separately, her monthly payments would be about $300 a month before accounting for strategies you could use to lower your AGI like contributing the full amount to 401k’s. I’m assuming that paying off $125,000 in law school loans takes at least 2 years for you, for a total cost of about $140,000. Maybe that’s high and takes into account too much in interest, but it’ll illustrate my point.

The 6 year period under PAYE filing taxes separately would result in a total cost of $24,500. Compare that to $140,000, and the difference is $115,500. Per year over 6 years, the cost savings from PSLF would be $19,250 per year.

But now factor in your retirement savings and things you could do to lower your AGI and thus lower the tax burden from filing separately. I think your $23,000 estimate could be too high, and I’d think it’d be worth it to pay an accountant $500 to check and see exactly what it would be. Yes you lose a lot of deductions and credits, but you’re smart about personal finance. You’d max your 401k at $18,000 a year and you’d max hers at $18,000 a year. That’s $36,000 in lower AGI every year. That probably drops your PAYE payment to $200 a month or even lower for her. That probably reduces the cost of filing separately for you.

Say the real total cost of filing separately is $10,000. I think that’s probably closer to what it would actually be since I work with folks with high income profiles and I’ve had people check with their CPA’s and they’ve told me that’s what it is. In that case you’d save a net of $10,000 a year for six years of after tax income for a total of $60,000 IF your wife stayed in the not for profit sector. On a pre-tax basis, that savings would be around $90,000.

PSLF is written into the promissory note. If she’s already being tracked towards the program, you have a very low probability she doesn’t get to take advantage of the program. Also I think you can amend taxes and file them jointly for up to three years afterwards, so if the strategy changes then you could change and alter the filing status and get a huge refund.

So financially, I actually think PSLF is still the better option based on the income numbers I’m guessing at. From a quality of life standpoint, it could make a ton of sense to just knock it out and be done. But I definitely think it’s worth studying the issue closely before you make the plunge of abandoning the strategy. Just my really detailed two cents haha.

@Travis – Thanks for such a long and helpful comment.

That’s unfortunate about your girlfriend’s consolidation at the end of residency. Good lesson there for everyone. New loan = PSLF clock starts over.

I think you’ve dramatically underestimated the amount of taxes I pay (of course, you didn’t have my real numbers to work with for this comment, so that makes sense) which is how you came up with a savings of about $90,000. But let me go over a few interesting points you raised.

First, you suggest that we could get the PAYE payment down to $200 a month. I think we can do even better. Most government employees have access to a ton of retirement account space. In our case, that’s a 401(k), a 457(b) and a pension. Add in a few other reductions to income from the Section 125 Cafeteria plans (e.g. health insurance premiums and transit ) and I’ll have her discretionary income barely above 150% of the poverty line. Discretionary income minus 150% of the poverty line times 10% brings her monthly payments down to about $20 a month.

Second, you calculated the cost of filing separately at $10,000 a year. This is based on a salary of $180,000 for me and a $60,000 salary for her. Our numbers are significantly higher, thus making the penalty even worse. Ignorining the deductions, if you assume we have a combined income of $240,000, every additional $1 taxed as MFS is taxed at the highest rate of 39.6%. If we were filing jointly, it would only be taxed at 33%. In other words, every additional dollar results in an additional 6.3 cents of tax. Or, for every $10,000 in income above $240,000 we pay an additional $630 in tax. At $340K of total income, that’s another $6,300 in tax. At $440K of total income, it’s another $12,300 in tax, etc. This is of course on top of the $10,000 you calculated. So our numbers might not actually be that far apart here.

What’s most interesting to me about your analysis is how PSLF could remain a consistently bad deal.

Let’s go back to your numbers, since they represent what a first year associate makes in Biglaw. Let’s assume we have a newly married couple just starting their jobs. They have a combined income of $240,000 and a $10,000 tax penalty as you calculated. Assuming 10 years of repayment, that’ll add up to $100K in extra taxes plus whatever loan payments they make over the 10 years plus additional taxes from any salary increase. That’s pretty close to $125K, which is the original loan balance had they just paid it all off. This isn’t even factoring in the other lost opportunities that come with MFS.

Of course PSLF can be a tremendously good deal to many people. I recognize that my details are just one fact pattern among many, but it’s becoming more and more clear that PSLF + married filing separetely + one high earner is a losing proposition.

Travis, if couples start with separately to qualify and then change to amend, what is the consequence?

Right now there’s not been a case I’m aware of where someone has gotten in trouble. but i would be conservative w it and amend only if it was an honest mistake or you have no loans.

Immediately when I started reading, I thought, “Wow, maybe they should file separately? But I’ve never recommended that to even one client – that can’t be right!” I’m glad you addressed the possibility and saved me the time of a long, complex comment!

Aside from that, no advice to offer. It seems like you’re considering all the right things. I typically recommend Millennial Moola’s Student Loan Analysis tool for these purposes: https://millennialmoola.com/2016/08/29/student-loan-analysis-tool/ But I’m fairly certain there is no value added in it for you, considering the math you’ve already done. May be helpful to a reader, though 🙂

Thanks for the link. It does look helpful. Millennial Moola is the same Travis that left the lengthy analysis above. I think our numbers match up pretty closely, which strengthens my resolve to pay it all off. Student loan debt is a such a pain in the ass, so this will probably be the big goal of 2017.

Haha thanks vigilante , I’m working on a more powerful version 2.0 so if you have suggestions as to what should be in it let me know !

Is there any way you could include a MFS vs MFJ feature in your sheet? That’s our big question right now. I used your sheet and it’s pretty handy but it doesn’t address this. Married, make $110k joint and wife is a teacher. It’s not clear at all which way to file is better. Thanks.

I think you may have to schedule an official consultation to get that level of analysis, but check with Travis for sure. No harm in sending him an email. He’s a sponsor of the site and his address is in the ad on the upper right hand corner.

Agreed that the MFJ v MFS question is tough and that there aren’t a lot of good tools out there to help you decide. Obviously, when you’re filing your taxes once you’re done you can hit the button to switch from one to the other to see the tax hit but that’s not super helpful when you’re trying to plan out what to do.

Have you tried TaxCaster to predict your tax burden? It’ll let you switch from MFJ to MFS to see how that impacts your situation.

https://turbotax.intuit.com/tax-tools/calculators/taxcaster/

Thx @BigLawInvestor. Darrin I’ve got a free tool that includes MFJ vs MFS, https://www.studentloanplanner.com/free-student-loan-calculator/

That doesn’t include the implied tax cost though bc I don’t have your AGI numbers built into the spreadsheet. If you’re at the point where you’re weighing the pros and cons a flat fee $199-$299 consult would probably be money well spent. Easy to make an error in the thousands of dollars with this stuff if you’re not in the weeds with the details

I have a bit of a different situation and would love your feedback. I have a very high amount of student loans (about 125K) and am in the IBR program. I do not work in public service or non-profit sectors so I do not qualify for any loan forgiveness programs. I have been married for 4 years and since then, my spouse and I have always filed separately to reduce my student loan payments. He makes a significantly higher income than me, about 160K. We do not combine all of our finances; we do have a joint account where we both contribute a percentage based on our income to cover household bills such as the mortgage.

In the last two years, we have both gone through job changes and income changes (higher for both). We have both had to pay at tax time every year since we got married. This year, we did a rough calculation of our taxes and he had to pay a significant amount (about 8K) due to filing separately. I think it’s incredibly unfair.

We have been kicking around the idea of amending our previous returns to reflect Married Filing Jointly (which we can do up to 3 years). This would hopefully recoup some of the thousands my husband still owes to the IRS (he has been on a payment plan). Can the Dept. of Education retroactively recalculate my student loans if I amend my tax returns? Will they ever know? Yes, I realize there are some ethical gray areas here. But in my case, I do not have access to my husband’s substantially higher income and do not think that he should be penalized for my high amount of student loans when we both take care of our own personal bills.

Thoughts or ideas? I can’t seem to find any literature on this at all. Surprising, considering the millions of people with student loans out there.

Les –

If you’re in IBR, you’ve demonstrated financial hardship, so you are in the loan forgiveness program where your loans will be forgiven at the end of IBR (although the amount will be taxable). It’s not necessarily the best path though, since it sounds like you both have enough money to pay off the loans.

The married filing separately tax brackets are extremely punative, so I’m not surprised to hear that you’re paying a significant amount of tax due to filing separately. I’m not a fan either. Given your high incomes, is there any reason why you’re not moving aggressively to pay off the loans? I’m not sure I see a reason for you to file separately (and pay the extra taxes) just so that you can separate your income from your spouse and make lower payments under IBR than you otherwise would have to if they looked at your income as jointly.

In other words, why not file jointly and use the tax savings to make payments on your loans? Does he have high loans too or is there some other reason why you’re making payments under IBR?

You seem like prime candidates to pay Travis a few hundred dollars to figure out the best plan for you (note: Travis at Student Loan Planner is a sponsor of the site but even if he weren’t I would mention him as a resource for you to consider, since he does this stuff every day and so can quickly analyze your situation for not a lot of money).

As far as amending your previous returns to change them to Married Filing Jointly, I’ve read about this as well. As far as I’m aware the Department of Education has no way to retroactively recalculate your student loan payments. I’m not going to comment on the ethics of it, but as you mentioned, you’re basically representing one thing for several years (which results in lower monthly payments) and then retroactively changing your representation later without having to make the higher payments. I don’t think a lot is written about this because anyone who is doing it doesn’t want to call attention to their situation.

I’m still wondering if you best bet wouldn’t be to refinance your student loans. If your income is ~$200K and you plan on paying off the loans, wouldn’t you want to take advantage of the lower interest rate and stop having to pay the extra taxes incurred when you file your taxes separately? Feel free to follow up on this post with more details and I’ll be glad to offer any ideas I have.

-Josh

I’m currently trying to decide if I should file separately from my husband for our 2017 taxes. I’ve been a teacher for nine years and foolishly didn’t do my homework on PSLF. All of this time, I thought my loan payments were going towards the 120 payments needed, before my loans would be forgiven. My husband is a union iron worker, so our combined salary is about $150,000. Iv’e currently been on the standard repayment plan & owe about $35,000. I can switch to an income driven repayment plan & basically start over with my 120 payments, but I’d have to file married separately. Is it worth it? Can I trust that this program will still be available in 10 years? We also have three children.

(BLI: Edited to compile multiple comments into one comment)

Most here seem to advise married couples to not file separately but my wife and I have found it to benefit us. I also have real data to back up the numbers for those in a similar situation for my wife and I. We live in the southern states. My wife is a school teacher (less than $50k gross) and I am a professional engineer (over $100k gross). She started PSLF in 2010 and we were married in 2012. So we have been filing separately since married in 2012 with a CPA and we requested the cost difference every year between a separate and joint return except for 2012 and 2013. Here is the breakdown:

2010 – $0 (wife was single)

2011 – $0 (wife was single)

2012 – $4,100? (no info for this year)

2013 – $4,100? (no info for this year)

2014 – $3,138

2015 – $4,805

2016 – $3,113

2017 – $5,347

And since we have 3 children, our monthly payments have been $0/mo. since 2015. At this rate, I’d estimate we will ultimately forfeit somewhere between $45k and $50k in potential tax return money. My wife’s balance on her student loan debt is $90k. So it seems to be working for us. Hope this helps others. I think the biggest piece of information to take from all this is to pay a CPA to tell you the answer. It is worth it.

T,

Do you co-sign on your wife’s annual re-certification every year with your income?

Why aren’t people considering ICR as the plan for high income earners?

A Direct Loan borrower who repays his or her loans under the ICR plan pays the lesser of: (1) The amount that he or she would pay over 12 years with fixed payments multiplied by an income percentage factor; or (2) 20 percent of discretionary income.

When I did the repayment calculator on Studentloans.gov, my payment was almost half that of the other IDR plans under ICR, and I will then qualify for PSLF.

Cara, maybe it would be helpful if you could elaborate with some hypothetical debt/income numbers. My question for you would be: How is paying 20 percent of discretionary income when you’re pursuing forgiveness better than IBR or REPAYE where you’d only be paying 15% or 10% of discretionary income?

I don’t pay 20% of my discretionary income on ICR. The program states “20% of your discretionary income, OR the amount of your fixed monthly payments on a 12-year loan term, whichever is lower.” I pay the latter, which is half that of what I was paying on REPAYE.

Go to the repayment calculator at studentloans.gov and plug the numbers to see for yourself. The calculator even predicts how much would be forgiven under PSLF. Best thing about ICR is you don’t have to be low income to qualify, unlike the other plans.

It really is the only plan for middle to high income earners. The others are for low to no income earners. I used to be in that category, and once I started earning a middle income in the federal government, my payments ballooned. I would end up paying the loans off quicker, but couldn’t really afford it. With ICR I can afford the payments, and will have a balance left over to be forgiven on PSLF in 7 years.

If you have significant loan balances and a high income your situation is different from mine, so take a look at the calculator.

Thanks again for leaving this comment. Cara and I took the conversation offline over email as we discussed the details of her salary and loan. For 99% of the cases I’ve seen, ICR doesn’t make sense but it looks like it is a viable option when your loan balance is low enough that you would otherwise pay it off in 10 years on an IDR plan (assuming that you’re pursuing PSLF).

It’s always a good idea to run your specific numbers in the studentloan.gov calculators.

Just wanted to weigh in on this thread as I’ve been dealing with PSLF for a while now. After eight years of repayment my wife and I got married and she makes significantly more than me. For us, it would be a close call if the potential $90,000 loan forgiveness would outweigh the additional income taxes she would pay over the next couple of years. However, my current payments are not calculated based on our joint income. When you recertify, there is an option to not have your payment based on your income taxes but instead provide alternate documentation of income. There are all kinds of reasons why (i.e. you take a new job making significantly less) but the bottom line is you can request your payment to be based on your income only. I’ve done this successfully for the past two years.

Thanks Tim. What payment plan are you on (IBR, REPAYE, etc.) and are you filing your taxes as married or separate? I’m assuming you’re providing the loan servicer something like your paystubs or W2 as an alternative form of income?

I’m currently on the Revised Pay As You Earn. I was on IBR but switched when the new plan came out (I missed PSLF credit for three payments because of this, but that’s another story). We file married filing jointly and yes, I provide income documentation through pay check stubs.

I’m in a relatively similar situation. My wife is a nurse with $65,000 federal loans and 5 years into the program. We file separately. Her monthly payment right now is $400 and will drop further once she renews for the following year. I always say “we should get legally divorced until this the debt is forgiven”

May I ask: what was her income and debt that made you abandon the program?

I found your site looking for direction in terms of retirement while filing MFS to lower the payments each month on IBR. I’m 36 and currently figuring out how to reach financial independence. I have about 4 more years of repayment. It’s just annoying to not be able to contribute to a Roth IRA if I am MFS based on the MAGI limits. I recall weighing the differences if I filed jointly with my spouse, and remember that the payments to PSLF would be way more that the tax return amount. But now that I want to think long term and about retirement, I’m considering filing jointly to be able to contribute to the Roth IRA. Hope what I said made any sense. If you have any thoughts, I’d love to read about them. I’m also interested in reading your update article when it is published. Thanks.

Thanks for writing in Minh. We are very close to the point of refinancing our PSLF loans and paying them off. We had a baby last year and my wife is staying home taking care of the child. While she may eventually return to a PSLF-approved job, we don’t know when that will be and it’s infuriating that we’re paying ~7% interest on the debt in the mean time. I’ll post an update once a decision has been made.

I’m not sure the benefit of getting access to a Roth IRA account is worth paying more actual dollars towards your student loans than you would otherwise have to under as a MFS filer. If I understood you correctly, you are basically asking whether it makes sense to make a higher student loan payment solely for the benefit of having access to a Roth IRA account.

You could run the numbers to be sure but my guess is that it’s best to lower your payments as much as possible until you hit forgiveness. If you’ve maxed out all of your other retirement accounts, then just stick the extra money into a plain brokerage account.

Those tax brackets you posted above do not reflect the current brackets for people who file married but separately. Current brackets put the tax liabilitees much closer to “single” filers.

John is right, doesn’t that mean the argument in the entire article falls apart? In 2020, MFS and filing single are the same except for the very top bracket.

This article was originally written in 2016. What specifically do you want to know now that the tax brackets have been changed by the TCJA? I can update / rewrite the article, although I’ve mainly left it as it is since it’s about a decision that was made in a moment at time.

Are you sure the tax bracket table you show is correct?

I am seeing a markedly different table at https://www.bankrate.com/taxes/tax-brackets/

The one that i am seeing doe NOT seem to indicate any appreciable penalty for MFS vs Single (until your income is $314,151 or more)